If you’re properly cynical, whenever you hear the name of a special interest group you should always follow it up with a sarcastic, “Oh really?” Because it turns out the names that groups give themselves have more to do with what they want you to think about them than with what they actually do.

For example: The Center for Science in the Public Interest. “In the public interest? Oh really?”

CSPI could more accurately be called “The Center for the Advancement of Vegetarianism”.

Let’s take a look at the May 2014 publication to see how they misuse and abuse science to make their point.

Do as I say …

Before you can make an informed decision, you need some facts. But in the nutrition field there are few facts that everyone can agree on. The problem is that to figure out the long-term effect of eating a certain way, you have to do a long-term study. That means either you control what a lot of people eat for a long time — good luck with that — or you ask a lot of people what they eat, and compare their diet to their health.

Since controlling what lots of people eat for a long time would be ridiculously expensive, if you could even do it, no one tries. The best you’ll find are studies that last for a few months, generally with a captive population. Literally captive — like prisoners, or patients at an institution of some kind.

The other option, instead of telling people what to eat you ask them what they eat. That’s called an observational study, because you’re just observing them. But unless you ask them every day (and you don’t) you’ll get really bad results. That’s why observational studies should be used to raise questions, never to answer them.

The entire first half of Fat Under Fire makes exactly this point, saying that there are no “good” studies showing people who eat more fat are healthier than people who eat more carbs. So clearly the second half will introduce all the studies that show the opposite, right?

Well, sorta.

Let’s have a trial

There’s an old rule for lawyers:

If you have the facts on your side, pound the facts. If you have the law on your side, pound the law. If you have neither on your side, pound the table.

Martijn Katan, the source being interviewed, puts all his stock in trials. Those are the tests where you control what people eat. But does he pound the facts or pound the table? Let’s see.

There are five references at the end of the article, and none of the specific claims mention which of these he is talking about. But what do those five studies show?

Ann. Intern. Med. 160: 398, 2014

There were 32 observational studies (512 420 participants) of fatty acids from dietary intake; 17 observational studies (25 721 participants) of fatty acid biomarkers; and 27 randomized, controlled trials (105 085 participants) of fatty acid supplementation.

In other words, this was not a trial. It was an analysis of the results of 76 previous studies, only 27 of which were trials. The other 49 were observational studies.

Circulation 2013.doi:10.1161/01.cir.0000437740.48606.d1

Recommendations were derived from randomized trials, meta-analyses, and observational studies evaluated for quality, and were not formulated when sufficient evidence was not available.

Again, this is not a trial. It is a policy recommendation that refers to many trials … and observational studies and meta-analysis.

PLoS Med. 7: e1000252, 2010

Studies were included if they randomized participants to increased PUFA for at least 1 year without major concomitant interventions, had an appropriate control group, and reported incidence of CHD (myocardial infarction and/or cardiac death)… From 346 identified abstracts, eight trials met inclusion criteria, totaling 13,614 participants with 1,042 CHD events.

Okay, now we’re talking. This meta-analysis is at least focusing on the type of high-quality trial you would need. However … when you get into the details you see that people were advised on what to eat more of and what to eat less of, but it wasn’t strictly controlled and it wasn’t “blinded”. A “double-blind” study is one where neither the subject nor the researcher knows who is on which protocol, or in the control group.

Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 77: 1146, 2003

The effects of dietary fats on the risk of coronary artery disease (CAD) have traditionally been estimated from their effects on LDL cholesterol. Fats, however, also affect HDL cholesterol, and the ratio of total to HDL cholesterol is a more specific marker of CAD than is LDL cholesterol… We performed a meta-analysis of 60 selected trials and calculated the effects of the amount and type of fat on total:HDL cholesterol and on other lipids.

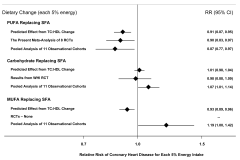

This one sounds good, too. But look at what it’s studying: the amount of HDL cholesterol in the blood. But click here to look at this chart from the previous study.

Image from Public Library of Science

Click to view larger

When replacing saturated fat (SFA) with polyunsaturated fat (PUFA) the change in HDL suggests a decrease in heart disease risk, and that is exactly what the trials and observational studies showed. But when replacing SFA with monounsaturated fat (MUFA), though the change in HDL suggests a decrease in risk the observational studies actually show the opposite.

That suggests HDL by itself is not a reliable indicator of heart attack risk.

N. Engl. J. Med. 363: 2015, 2010

In a multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, we randomly assigned 4837 patients, 60 through 80 years of age (78% men), who had had a myocardial infarction and were receiving state-of-the-art antihypertensive, antithrombotic, and lipid-modifying therapy to receive for 40 months one of four trial margarines: a margarine supplemented with a combination of EPA and DHA (with a targeted additional daily intake of 400 mg of EPA–DHA), a margarine supplemented with ALA (with a targeted additional daily intake of 2 g of ALA), a margarine supplemented with EPA–DHA and ALA, or a placebo margarine.

…

The rate of adverse events did not differ significantly among the study groups.

So this one showed … no effect from any of the things they tried.

That doesn’t sound really compelling, does it?

One meta-analysis of mostly observational studies, one policy paper based mostly on observational studies, one meta-analysis of trials that weren’t randomized, one meta-analysis of well-constructed trials that (unfortunately) are looking at a marker that doesn’t correspond well to actual health outcomes, and one well-constructed trial that shows no effect whatsoever from anything they tried.

I may be presenting the worst possible interpretation of every single one of these citations. But Katan and CSPI haven’t pointed to specific instances that support any of the claims Katan made. For a guy who spends so much time talking about how there aren’t good studies to back up someone else’s position, he sure doesn’t provide much evidence for his own.